I love fantasy fiction for numerous reasons, and one of the big ones is that it has no set rules. You can create whatever stories you want — stories with dragons and wizards, time running backwards, conversations with God, whatever you could possibly imagine. As this is such a diverse genre, it’s fascinating to read fantasy authors talk about why they like fantasy and what they feel is most important when writing a good fantasy story. As I mentioned previously, there are no set rules for fantasy. Any time someone says “fantasy must have this” or “fantasy must not have this,” I can think of numerous good tales that break those rules. That said, looking at each person’s personal “do’s and don’t’s” can give a lot of insight into each author’s thought patterns and help to give aspiring writers some ideas of what direction they want to go. I do not look on these as “must have” or “must not have” but “perhaps” or “perhaps not.” They are rules that have certainly worked for the people in question.

H. G. Wells

Creator of such classic SF as The Time Machine, The Island of Dr. Moreau, War of the Worlds, and The Invisible Man. Though he is generally considered a science fiction author instead of a fantasy one, Wells in contrasting himself to Jules Verne certainly considered his work fantasy. He was not interested in exploring real scientific possibilities but in using a thin veneer of science to give his fantasy stories slightly more plausibility (The Invisible Man is basically about a sorcerer cursed by his own spell, only making it a potion to help suspend the reader’s disbelief).

Well’s Rule: That anything in the story not the fantastical part should feel very normal, mundane. Even boringly so. If everything else seems so conventional, it makes the fantasy elements seem more fantastical in contrast.

Commentary: Contract between the natural and the supernatural certainly helps to make the supernatural seem stranger. However, I wonder what Wells would have said about stories set entirely upon alien worlds (such as Dan Simmons’ Hyperion) or within mythopoeic stories about realms entirely created by the author (such as Tolkien’s Middle Earth). That said, even they have elements of normalcy — habits and routines in their characters, mundane needs — that we can relate to, and are necessary for grounding the events and thus making the fantasy believable.

The Message: There should have some elements of the normal and the mundane to ground the supernatural elements. Moments of mundanity can make the fantasy elements more fantastical by comparison.

H. P. Lovecraft

One of the most prolific (though disorganized) world builders of fantasy; in his case he built an entire universe. His most famous creation is the monstrous proto-god Cthulhu (and indeed, the “Cthulhu Mythos” is the most common term for the setting of his stories), but Lovecraft created a whole dark pantheon of gods and demigods, demons and monsters, and a history of the universe that stretches deep into the prehistoric past and cosmic future — a history in which humanity plays an infinitesimal role.

Lovecraft’s Rule: Paradoxically, Lovecraft was a devote and committed atheist who saw fantasy (or “weird fiction,” as he called it) as a way to achieve a feeling of numinous wonder and awe. Though he is mainly known as a horror author, he actually felt producing this sense of awe, that the reader was touching some new deeper reality, was more important than terrifying people. Just that Lovecraft found it easiest to produce awe through fear, and thus most of the stuff he wrote was horror. This desire influenced his ideas of how fantasy should be written. He felt that often the best fantasy writers were atheists like himself, who did not believe in the paranormal — because then they choose supernatural elements for their story based on what they feel would be the most dramatically relevant, not what they feel is “real,” and furthermore, the supernatural then feels strange, unreal, and incomprehensible, whereas a practicing occultist would often perceive the supernatural as matter-of-fact and even mundane. Lovecraft conceded that many of his favourite fantasy authors, such as Algernon Blackwood and William Hope Hodgson, were believers and even practitioners of the occult. but Lovecraft also felt that these people’s writings were better when they were bringing things from their own imagination rather than from their spiritual beliefs.

Commentary: One can certainly see Lovecraft’s point. Fantasy is at its most powerful when it is engaging the reader with its emotional intensity, moving the reader into a different realm. Someone’s spiritual beliefs can certainly get in the way of that, resulting in something that seems dull or pedantic, rather than strange. For example, when Hodgson’s stories start to approach real occult beliefs, they lose a lot of their strength, and appear more mundane. That said, authors incorporating their own spiritual beliefs have also added a lot of depth and intensity to their work. It is impossible to imagine C. S. Lewis’ SF without its ascendant Christianity or Grant Morrison’s graphic novels without his bizarre chaos magick. But then, in their works the supernatural is never mundane or conventional. Lewis’ angels are just as numinous and unknowable as Lovecraft’s dark gods (though more supportive of humanity) while Morrison’s magick is as weird as anything in Lovecraft (weirder in most cases).

The Message: Do not be bound by your own beliefs when creating fantasy. You certainly can draw upon them, and that can give your writing a lot of depth. However, you should not be restricted by them. Ask yourself how should the supernatural be displayed in the way that best serves the story.

Montague Summers

A highly eccentric clergyman at the dawn of the 20th-century, Montague Summers was most famous for his various books on occult subjects such as vampires, werewolves, and witches, and for his belief that such being exist and form the Devil’s army. Summers was also one of the few people of the 20th-century who spoke in favour of Europe’s various witch-hunts and did the first English translation of the witch-hunter’s manual Malleus Maleficarum. He also adored horror literature and compiled three anthologies of supernatural stories.

Summer’s Rule: In sharp contrast to Lovecraft, Montague Summers argued that in order to write a good supernatural story, one must believe in the supernatural. If the author does not believe in it and take it seriously, then its presence in the story will lack any depth, believability, or energy, “the spell will be broken.”

Commentary: This is a bold claim and one that Summers quickly walks back just after he says it. He felt the best fantasy author was Sheridan Le Fanu (most famous for “Carmilla”), but as Le Fanu had no real belief in the paranormal, Summers shifts his claim slightly to say that even if the author does not literally believe in the supernatural, he must still respect it on some unconscious level — which Summers argues that Le Fanu does. Though Summers raises an interesting point, there have been numerous potent fantasy pieces by staunch atheists. The aforementioned H. P. Lovecraft wrote some of the most influential weird fiction of all time, and numerous other atheist authors have written powerful pieces and evocatively believable words, from Michael Moorcock to Douglas Adams, Terry Pratchett to Warren Ellis.

The Message: Every author must take his world seriously. It doesn’t just apply to fantasy or science fiction authors. If you are writing a romance or a western, the characters, their struggles, and the story need to matter to you. They need to seem real. A fantasy author must believe in his world; that’s very important. That said, he doesn’t need to believe that all the elements of his world exist in ours as well. Discworld clearly mattered to Terry Pratchett on a fundamental level; Dirk Gently’s encounters with the impossible were important to Douglas Adams. The fact neither of those men believed in the paranormal didn’t change that. H. P. Lovecraft’s uncaring universe is powerful because it is fueled by his atheistic existentialism just like C. S. Lewis’ strange angels are powerful because of his own nervousness of gazing at God’s face. There is certainly room for both in the genre.

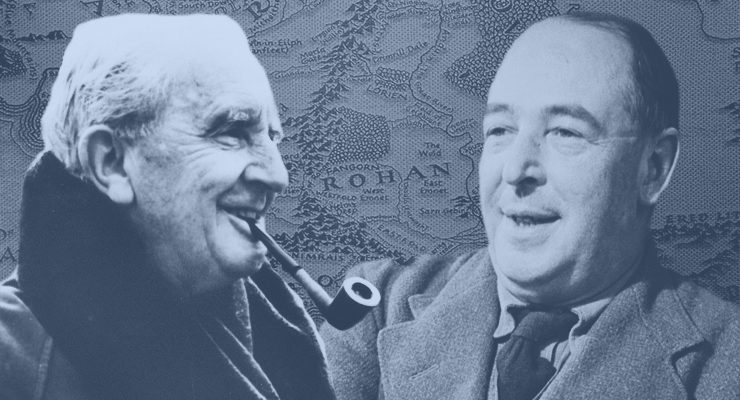

J. R. R. Tolkien

The fantasy author who needs no introduction. For many people, The Hobbit was their introduction to fantasy novels and The Lord of the Rings is their defining fantasy tale. Tolkien is the whole reason why many people think elves, dwarves, and goblins are necessary for magical worlds.

Tolkien’s Rule: J. R. R. Tolkien coined the term “mythopoeia” (“myth-making”) to refer to the process of creating your own fictional world with its own geography, history, mythology, etc. He believed very strongly in this idea, which encouraged him to produce Middle Earth, certainly one of the most detailed and believable fantasy worlds. As part of this drive to myth-make, Tolkien felt that a fantasy world needs to be internally logical and self-contained, where everything fits together thematically and seems true to itself. As part of that, he felt fantasy fiction is more effective if it was free of any explicit supernatural elements that match what the author believes in. For example, Tolkien was a Catholic and believed in literal angels and demons, and so he went out of his way to have any good or evil spirits showing up in his stories be very different from “real” ones, instead appearing as ancient demigods and giant animals. He disliked the explicit Christian elements in King Arthur stories and hated Narnia for its very prominent Christian imagery, its mixing of creatures from numerous mythologies (Greek satyrs standing side-by-side with Norse dwarfs and a Babylonian-esque man-headed bull), and most of all its presence of Santa Clause, a being from modern Christian folklore.

Commentary: Tolkien had some very specific ideas of what he wanted a fantasy world to be. He wanted it to be totally different from our own, with not just its geography and history but its cosmology and mythology quite unlike ours. But one does not need to create everything to tell a powerful story. I think having a lot of focus is really important in your own writing — you should have very specific ideas about what you want your fantasy world to be. However, there are big differences between the specific ideas you have about the stories you want to write and the world you want to create and the specific ideas you have about the stories others should write. There is a lot to be said for Lewis’ modern supernatural fiction (such as Screwtape Letters and That Hideous Strength), which draw upon his own beliefs, as well as numerous fantasy stories that a world that combines the sensibilities and myths of numerous cultures (such as Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn or Neil Gaiman’s Sandman). No author should feel compelled to model his or her writing process after Tolkien.

The Message: Think about the reality of your fictional world and think about the rules that govern it. Do not bring in elements that break the rules of your reality, but also do not feel bad about developing the world your own way. The Last Unicorn remains one of the most powerful fantasy novels ever written, despise the fact that it has a character who claims to be the historical basis for Robin Hood and who name-drops John Henry, because that fits the strange timelessness of the world. Write what makes sense to your world, not someone else’s world.

C. S. Lewis

Most famous for the Chronicles of Narnia, though C. S. Lewis also wrote a wide variety of strange tales of fantasy and science fiction for grown-ups, including his Cosmic trilogy, the Screwtape Letters, and ‘Til We Have Faces. A phenomenally well-read person, Lewis was intimately familiar with a wide variety of fantasy literature, and incorporated a wide variety of influences into his own work.

Lewis’ Rule: He felt that any fantasy or science fiction story should focus primarily on the fantasy elements — they must be front-and-centre to what is going on. He had no interest reading a romance that just happened to be set on another planet or a murder mystery on a parallel universe. The focus should be on the protagonist exploring this strange reality. Thus, he was very interested in the first visit to a planet, but not the second visit — for with the second visit, the experience would not be fresh and strange for the protagonist, and thus not for the reader. This can be seen in Narnia, where in each story the characters find themselves either in a totally different country or after a long period of time (such as a 1000 years), so that each appearance is fresh. Likewise, in the Cosmic trilogy, each planet is only visited once. On a similar note, Lewis feels that fantasy protagonists should be relatively simple psychologically, with not much time spent exploring a lot of deep internal struggle – for that moves the focus away from the exterior fantasy world.

Commentary: One can certainly see where Lewis is coming from. Like Lovecraft, Lewis is perhaps most interested with having fantasy produce a particular “feel,” creating a potent numinous experience. Though Lewis’ characterization and plot may sometimes feel a little flat, nothing beats his description, the mood and imagery of his scenes. One can definitely see the important of keeping the fantasy front-and-centre. If your story does not concern itself too much with the fantasy elements, then why make it fantasy at all? And, of course, there have been numerous marvelous works of fantasy literature that feature characters with relatively little interiority: Lemuel Gulliver of Gulliver’s Travels, Alice of Alice in Wonderland, Lewis’ own Elwin Ransom of the Cosmic trilogy. They exist mainly to be the eyes of the reader in exploring the fantasy world. That said, the “Guards” series in Discworld are some of the best fantasy ever written, and are police procedurals in a fantasy city with much of the conflict internal person vs. self, and which is a world and even a city that Pratchett returns to again and again, but still somehow always feels fresh. The comic Elfquest Wendy and Richard Pini also engages in deep psychological exploration, and in that case the same community is returned to again and again over numerous generations, but in a way that never makes it feel mundane.

The Message: The fantasy elements must be important to the story and the story should feel magical not mundane. That said, there are numerous ways that this fantastical element can be maintained, whether it is about a person exploring a new fantasy world or about someone trying to live their life in a strange place we have met before. Always think about how you want to present it in your own story.

Fantasy is an amazing genre because you can do literally anything you want with it. Everyone has their own idea about what fantasy is and what they like about it. Understanding an author’s reasons behind their own fantasy ideas can be very insightful in learning why that author makes the choices that they do, and it can give other authors insight into their own fantasy. That said, perhaps the most important piece of advice for writing fantasy or anything else is that you must make it your own — write it your way, whatever is comfortable to you. Don’t write it the way someone else wants it written.