Tags

“The fallen angel becomes a malignant devil. Yet even that enemy of God and man had friends and associates in his desolation; I am alone.”

-Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

To honour Mental Health Month and my own struggles with anxiety and depression, I will be exploring various examples of characters with mental issues throughout literature and popular culture, starting with perhaps the most gut-wrenching: Frankenstein’s Monster.

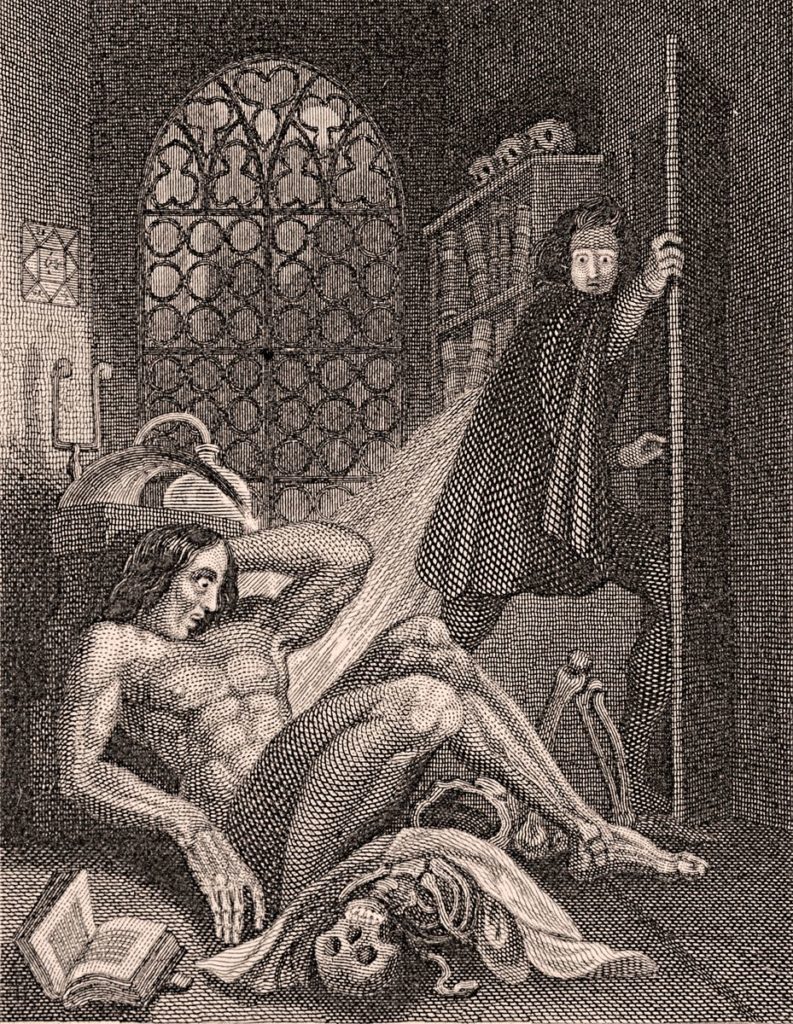

Arguably the greatest horror novel ever written, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein produced the most compelling horror icon of all time. The Monster himself is terrifying — a huge and hideous product of an unnatural birth — but also someone who we feel such empathy for. It is telling that the two most iconic version of the story (the Mary Shelley novel and the James Whale movies with Boris Karloff) initially envisioned Dr. Frankenstein as being the protagonist and named the story after him, but most people think of the title as referring to the Monster rather than the scientist because the Monster is far more memorable, and it is he who feels like the real protagonist.

His suffering is anyone who has suffered from mental issues such as depression or anxiety can sympathize with. The Monster feels different, unnatural, wrong — he knows the population of the world is divided between himself and everyone else, that he has been made imperfectly, falsely. When I am at my darkest, I myself often feel like a “patchwork man,” a bunch of pieces that don’t seem to quite fit together, a soulless automaton rather than a real person.

When in the depths of depression, one feels unloved, incapable of being loved, which is the great curse of the Monster. He has been defaced by the Mark of Cain, though unlike Cain, it’s not a punishment for any crime he did. He is desperate for a place in the world, but cannot find it anywhere he goes. The more the Monster is rejected and persecuted, the more his hope is consumed by desolation and rage. Many people who experience mental issues feel intense frustration for who they are, that they are fighting against themselves, against pieces of their mind that don’t seem to quite fit together. The Monster knows why they don’t fit — because he was made improperly by a person who thought himself God.

Dr. Septimus Pretorius: Do you know who Henry Frankenstein is, who you are?

The Monster: Yes, I know… made me from dead… I love dead… hate living.

–Bride of Frankenstein

Speaking for myself, I have always found Karloff’s interpretation of the Monster to be even more compelling than the original. His treatment in James Whales’ Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein is one of the most emotionally intense performances in cinematic history. Perhaps it’s because the Monster here feels closer to me. He’s not just broken in body as Shelley’s Monster is, but broken in head.

Karloff’s Monster has a hard time understanding the world, a hard time communicating. He has impulses he cannot understand, which often take control of him (here derived from a murderer’s brain that he was cursed with). Shelley’s Monster is always very cognizant of all the damage he caused, coldly striking in vengeance against a humanity that rejected him, but Karloff’s Monster is confused. He drowns a girl under the mistaken belief that she’ll float as happily and prettily as the flowers that he and she were tossing into the water. He happily follows Dr. Pretorius when the mad scientist suggests that he can make a friend for the creature, and then howls in frustration and betrayal when that doesn’t happen. Karloff’s Monster was brought into the world unable to understand it, and remains baffled and pained by whatever’s going on. He is us as we try to claw our way through life, seeing other people who find it so much easier than we do. He is us living in a world that seems to be built for other people.

I have screamed at the sky, demanding the universe tell me why I was built this way, why my brain seem to respond to things differently from how other people do. Why does this storm of negative emotions seem to crash through my body? Why do I feel false, broken? The Monster knows why. Because his creator built him not knowing what exactly he was, then tossed him into the cold, leaving him unable to know how to cope with existence.

In a weird way, he fulfills a strange fantasy I’ve had — wouldn’t it feel nice to punish the God that made you such a broken person? Who decided that you should have a mental storm most other people don’t? Wouldn’t it feel good, just for a little bit — to drag that being down to the depths of depression that you regularly god? Of course, it wouldn’t make anything better. In the novel, the Monster tortures Frankenstein, murders everyone he loves, and then forces Frankenstein into a long and tortures death in the snows, and seeing the corpse just makes the Monster sob, makes him rant about how pitiful he is, and decide to burn himself to death with Frankenstein’s corpse at the North Pole. In Bride of Frankenstein, the Monster does the opposite, deciding that Frankenstein and his wife should go and live because he is “alive,” whereas the Monster and his bride are “dead…. We belong dead.” I feel that the Monster saving Frankenstein has less to do with any real forgiveness and more him wanting someone to remember him positively — to get some satisfaction as he kills himself.

The Monster: We belong dead.

–Bride of Frankenstein

The horror of Frankenstein is not that we will be attacked by the Monster, but that deep down we are the Monster. That we are soulless automatons who have been “made wrong,” beings damaged and then discarded by our creator. We have bodies that don’t do what they’re supposed to, minds that don’t do what they’re supposed to, impulses that drive us mad, and there is no one else like us, and if there were, they would reject us too (as the Bride rejects the Monster), for who could truly care for us — even fellow freaks would try to be with normal people. We are, as Karloff’s monster succinctly said, “dead.”

If the Monster can be a metaphor for mental issues, that feeling of lonely brokenness that frequently haunts our brains, then what is it ultimately saying about those issues? It is how they can possess the person who feels them, take over their lives. How it leads to fear, to frustration, to rage. How it can make us lash out against those we blame for our pain. How in the end, when it takes us over, the person we most lash out against is ourselves.

Though certainly not the most empowering image of depression and mental issues, perhaps nothing better captures the isolation and imagery that it produces than Frankenstein. We are all Frankenstein’s Monster, but unlike the Monster, we cannot punish our creator. We can only hurt ourselves. At the end of both the novel and Bride of Frankenstein, the Monster commits suicide — either burning himself alive along with Frankenstein’s corpse in a funeral pyre or pulling a convenient switch in the lab to blow him to atoms. Are the stories saying that this is the only possible ending for those who feel dominated by mental issues?

The ultimate motivation for the suicide is desolate loneliness. The Monster feels no one cares about him, he is truly alone. However, we in the real world who deal with these issues are not alone ourselves. There are other people out there who suffer from similar issues, and we can reach out to each other. We can tell each other that we are not dead, we are not automatons, robots, or zombies. We are human, we are people. We are not broken. We are merely different. And we are not alone. Maybe often we with mental issues feel like we cannot save ourselves, but we can save others who are similarly touched — we can save them because we understand what they’re going through, because we can show them they are not alone. Unlike Frankenstein Monster, we are not alone.