Tags

Here are three (or rather four) different races for a version of Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition based in Welsh folklore. Though these are the most obvious ones, other races could be selected as well with the DM’s will. For example, the triton from Volo’s Guide to Monsters could work well as merfolk and the shifter from the D&D website could be a good fit for werewolves and even Saxon werebears and strange Annwn wereboars.

Note that the language “Annwn” is that of the fey of the Otherworld, and thus replaces the normal D&D language “Sylvan.”

Half-Giant

Half-Giant

Before humans ruled, Britain and Ireland belonged to the giants. Then the Picts came, but these folk saw the wisdom with allying with the lords of the land. Even marriages were made, with giant chieftains taking Pictish brides and Pictish chieftains taking giant brides. Then Brutus the Trojan brought his people to the island and warred against giants and Picts alike until he conquered the giant king Albion and claimed the island for his people – who became known as the “Brythons” in his honour. However, there are still giants in Britain – especially in the far north above Hadrian’s Wall. Most despise the Brythons, though are content to be left alone in the wild places. Still, some do make they wrath known.

And then there are the half-giants.

Between Human and Giant

Though many half-giants are the product of a human and a giant parent, the bloodlines of Picts and giants have been so intermingled that it is not uncommon for a half-giant to have two Pictish parents or two giant ones. Though much shorter than regular giants, half-giants are still tall, imposing figures with powerful bodies and long limbs. Their hair and eyes can be a variety of colours, but are most often black or dark brown. Though not as prone to mutation as regular giants, some are still born with a single eye or leg, huge tusks, or unusual coloration. They often dress like the community they’re trying to fit in with – like a giant when with giants, like a Pict when with Picts.

Hermits and Tribesfolk

There are not enough half-giants to form their own communities, so if they wish the company of others, they must associate with either giants or humans. In some tribes they are welcomed, though in others they face derision – this is especially true among giants, who value physical strength so highly. Scornful giants call them “half-breeds” or “runts.” They frequently receive more respect among Picts – Caw, one of the greatest Pictish kings, was a half-giant. It is often easier to be perceived as an unusually large, powerful human than an unusually small, weak giant. Occasionally a half-giant gets raised by humans who are not Picts – for example, King Arthur’s wife Gwenhuvar was raised a Brython by Lord Cador despite being the daughter of Ogrfran the Giant.

Like many giants, many half-giants become hermits. In some ways they can do it far more effectively, for the smaller half-giants can disappear into the wilderness much better than their larger cousins can. They adapt well to heights and the cold, and so are most often found in mountain ranges, though they also make their homes in dense forests and hidden valleys.

Half-Giant Characters

Barbarian is by far the most common character class for half-giants, as it is not only common in giant and Pictish cultures, but also gives them useful wilderness survival skills and voice to the rage and frustration that often dwells within them. Certain half-giants who develop a more spiritual approach to the natural world may become rangers instead; these often befriend creatures of great physical power: boars, bears, and giant serpents. Not surprisingly, an unusually large proportion of giant-soul sorcerers are half-giants. Druids and warlocks are not uncommon either. The druids will often be shamans in the Pictish tradition that follow the Circle of the Shepherd, but mountain or forest Circle of the Land are frequent too. Warlocks will usually have pacts with the Archfey or the Undying (spirits of dead giants and Picts). Other character classes are rare and often involve contact with other cultures.

HALF-GIANT TRAITS

Half-giants share a number of traits in common with each other.

- Ability Score Increase. Your Strength score increases by 2, and your Constitution score increases by 1.

- Giant: Half-giants are giants not humanoids.

- Age. Though not as long-lived as many other giants, half-giants can still live longer than humans. They reach maturity at 15 and often live to at least 200 years.

- Alignment. Their raging spirits and solitary natures means that most half-giants tend more towards chaos than law. Chaotic evil half-giants are pitiless raiders who attack others to get what they want, whereas chaotic neutral ones are usually either solitary recluses or wanderers. However the more tranquil hermits among them are often true neutral.

- Size. “Runts” compared to regular giants, half-giants are generally between 7 and 9 feet tall and weigh between 280 and 400 pounds. However, certain ones (such as Queen Gwenhuvar) are even shorter, perhaps a mere 6 feet tall. Your size is Medium.

- Speed. Your base walking speed is 30 feet.

- Menacing. You gain proficiency in the Intimidation skill.

- Savage Attacks. When you score a critical hit with a melee weapon attack, you can roll one of the weapon’s damage dice one additional time and add it to the extra damage of the critical hit.

- Long-Limbed. When you make a melee attack on your turn, your reach for it is 5 feet greater than normal.

- Powerful Build. You count as one size larger when determining your carrying capacity and the weight you can push, drag, or lift.

- Mountain Born. You’re acclimated to high altitude, including elevations above 20,000 feet. You’re also naturally adapted to cold climates, as described in chapter 5 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

- Languages. You can speak, read, and write either Brythonic and Giant or Brythonic and Pict (depending upon which culture you were raised in). Many learn both Pict and Giant.

Ellylon

Ellylon

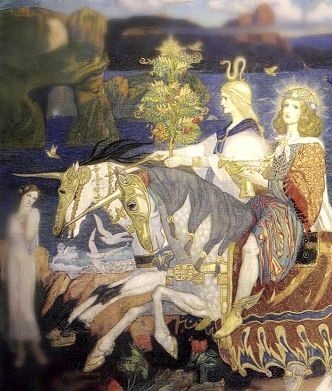

There exists a world beside the moral one, a world often reached through mysterious mist and hollow hills, across the ocean and deep under the earth. This world is Annwn, the Otherworld. It is not above Earth like Heaven or below it like Hell – it is beside it and through it. It is the realm of the fey.

The lords of Annwn find the words “fey” and “fairy” offensive (as well as the Saxon term “elf”), so various euphemisms are used instead: the Good Neighbours, the Fair Folk, the Shining Ones, the Lords and the Ladies, or most commonly the Tylwyth Teg – the “Beautiful Family.” Their term for themselves is the “Ellylon.” They are often curious about humans, and so cross-over to the mortal to visit them, while others prefer instead to draw mortals into their own world.

The Fair Folk

Ellylon appear as tall, lithe humanoids of unearthly beauty. In their natural form, their hair is always yellow (though depending on the ellylon, it may be a shining gold, the rich colour of wheat, or a paler platinum) and their eyes are hypnotic and golden. Their skin is pale, often almost white, and their features are angular and pointed, including their ears. Ellylon clothes are usually rich and elegant, coloured white and gold. However, they all possess the power to appear perfectly human, and often will wander among mortals in that form.

Lords of the Otherworld

As befits many of their titles, the ellylon are the lords of the fey. Their mightiest include Arawn, Gwyn ap Nudd, Morgen and her sisters, and other rulers of Annwn. Lesser ellylon are the courtiers, warriors, and hunters of the courts, following the dictates of their masters. They are known for their whimsy and for their pride, for most ellylon consider other beings – giants, humans, goblins – to be their clear inferiors. Many grow bored of the Otherworld, and seek to enter the mortal plane for sport. Most will only engage in brief sojourns but some choose to remain among humanity. These are usually the least influential ellylon, who believe they will be prominent among mortals than among other fey.

Ellylon Characters

Ellylon are masters of magic, and produce many powerful fey-born sorcerers, fey-pact warlocks, and bards of all sorts. Those more martially inclined are generally ancient-oathed paladins or rangers, or fighters that become arcane archers or eldritch knights. However, they are ruled by whim, and could end up taking on almost any class. However, no ellylon can become a mystic or a devoted-0athed paladin. They do not have souls as mortals do and cannot comprehend the ways of God.

ELLYLON TRAITS

Ellylon share a number of traits in common with each other.

- Ability Score Increase. Your Charisma score increases by 2, and your Dexterity score increases by 1.

- Fey: Ellyllon are fey not humanoids.

- Age. Ellyllon reach physical maturity at the about the same age as humans. As fey, they will never get old or die of old age. An ellyllon 1000 years old is just as healthy as she was at 20.

- Alignment. The lords of the fey have little concept of good and evil and their moods can be as changeable as a breeze, compassionate at one moment and cruelly vengeful the next. Most are chaotic neutral and they are almost never lawful.

- Size. Ellyllon are tall, usually from under 6 to over 7 feet, and with slender builds. Your size is Medium.

- Speed. Your base walking speed is 30 feet.

- Darkvision. Accustomed to twilit forests and the night sky, you have superior vision in dark and dim conditions. You can see in dim light within 60 feet of you as if it were bright light, and in darkness as if it were dim light.

- Unnatural Beauty. You have proficiency in the Persuasion skill. Whenever you make a Charisma (Persuasion) check that takes particular advantage of your physical attractiveness, add double your proficiency bonus to the check instead of your normal proficiency bonus. Though you always possess the Persuasion skill no matter what form you take, the second option can only be employed in your natural ellyllon form.

- Human Form. You can at will change your form to appear human. Whenever you use this ability, you take the same unique human form – it resembles you though with all fey traits replaced by human ones and your beauty is no longer unnatural (though still striking). The only thing that you can vary when you transform is your coloration – eye, hair, and skin colour. You can stay in your human form as much as you wish, but it is a magical transformation, and so is affected by dispel magic and similar effects.

- Age Immunity. You are immune to any aging magic.

- Cantrips. You know two cantrips of your choice from the bard and/or warlock spell lists, as well as the cantrip Otherworldly Door. Charisma is your spellcasting ability for them.

- Languages. You can speak, read, and write Brythonic and Annwn.

Goblin

Goblin

While the ellylon rule and hunt, the goblins serve. By far the most populous kind of fey, they perform all the various tasks that the Fair Folk consider too degrading or dull to perform. The two most prominent kinds are the hearth goblins (“booka”) and the mine goblins (“coblynau”).

Rough and Crude

In appearance, the goblins are the opposite of the ellylon. Instead of being tall and graceful, they are short and awkward. Instead of being inhumanly beautiful, they are inhumanly ugly. Their faces are wide, their mouths huge, their voices high-pitched, their eyes large and goggling. They look like caricatures of humanity, and even though they are actually very dexterous, when they move it often seems animalistic, like a scurrying rat or lopping rabbit. Some have animal features, such as horns, fangs, or tails. Their behaviour is generally blunt and unsophisticated, with a strong liking for practical jokes.

Many goblins seek self-expression through their costumes, wearing garish outfits that combine particular clashing styles. Those who live around mortals will frequently combine the looks of those individuals they admire.

Fey Servants

In Annwn, the goblins are menial servants. Booka are house servants – maids, butlers, cooks – while coblynau are miners. Many are content to serve their ellylon masters, but others flee to the mortal realm. After all, though their magic is considered insignificant in the Otherworld, it can produce respect and fear among mortals.

Goblins in the mortal realm generally fall into one of fours categories. There are goblins being sent on missions by their fey masters. There are those (especially booka) who seek to serve humans as they did ellylon, believing that these masters will give them more respect. There are those who instead toy with mortals for their own amusement, playing tricks on them. And there are those goblins that instead strive to be treated as equals, such as the warrior-bard Eiddilig, who joined King Arthur’s court.

Goblin Characters

Goblins favour classes that reward stealth and cunning. They are frequently rogues and bards, and sometimes rangers or fey-pact warlocks. Though in theory they could be almost any other class, they cannot be mystics or devoted-oathed paladins. Like all fey, they cannot channel the power of God.

GOBLIN TRAITS

Goblins share a number of traits in common with each other.

- Ability Score Increase. Your Dexterity score increases by 2.

- Fey. Goblins are fey not humanoids.

- Age. Goblins reach maturity surprisingly early, often at 10. As fey, they never die of old age. Very old goblins (such as 500 or 600 years) will often be very wrinkled and wizened, but they are still just as healthy as they ever were.

- Alignment. Goblins are often less whimsical than ellyllon and can be neutral as often as chaotic neutral. Those who travel to the mortal realm frequently form a bond with humans, either helping them in the home (for booka) or in the mines (for coblynau) – these goblins are most often neutral good. However, others realize they can toy with humans like the ellyllon toy with them, becoming chaotic neutral or even chaotic evil.

- Size. Goblins are between 3 and 4 feet tall and average around 40 pounds. Your size is Small.

- Speed. Your base walking speed is 25 feet.

- Age Immunity. You are immune to any aging magic.

- Naturally Stealthy. You have proficiency in the Stealth skill.

- Languages. You can speak, read, and write Brythonic and Annwn.

Subraces. Two subraces exist: booka (hearth goblins) and coblynau (mine goblins).

Booka

- Ability Score Increase. Your Wisdom score increases by 1.

- Cantrips. You know the Mending and Otherworldly Door cantrips. Wisdom is your spellcasting ability for them.

- Dark Vision. You can see in dim light within 60 feet of you as if it were bright light, and in darkness as if it were dim light.

- Tool Proficiency. You gain proficiency with two artisan’s tools of your choice: brewer’s, carpenter’s, cobbler’s, or cook’s. If you then acquire one of these proficiencies a second time (such as through a background), add double your proficiency bonus to the check.

- Speak with Small Beasts. Through sounds and gestures, you can communicate simple ideas with Small or smaller beasts.

Coblyn

- Ability Score Increase. Your Constitution score increases by 1.

Cantrips. You know the Mold Earth and Otherworldly Door cantrips. Wisdom is your spellcasting ability for them. - Superior Dark Vision. You can see in dim light within 120 feet of you as if it were bright light, and in darkness as if it were dim light.

- Tool Proficiency. You gain proficiency with mason’s tools. If you then acquire this proficiency again (such as through a background), add double your proficiency bonus to the check.

- Stonecunning. Whenever you make an Intelligence (History) check related to the origin of stonework, you are considered proficient in the History skill and add double your proficiency bonus to the check instead of your normal proficiency bonus

Half-Demon

Half-Demon

Some times demons or the Evil One himself will seduce mortals for their own dark purposes. Such unions will sometimes produce children, beings generally known as “half-demons.” Such wretched creatures are treated as tieflings from the Player’s Handbook with the following exceptions:

- Depending upon their demon sire, the exact nature of the half-demon varies. You can use any of the tiefling variants from Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes.

- All half-demons are proficient with the disguise kit.

- Half-demons look much more human than conventional tieflings, and will generally only have one or two demonic traits that can be hidden with a successful disguise kit proficiency roll. Such traits might include small horns, reddish skin, pointed ears, fangs, a forked tongue, or other small yet disquieting features.