Call of Cthulhu is the role-playing game based on H. P. Lovecraft’s series of famous short stories of nihilistic dark gods and monstrous aliens. Here’s how I would link the various forces of Lovecraft’s universe with Welsh mythology.

THE GODS

CTHULHU

There are references to the gods Llyr and Dylan ruling undersea kingdoms off the cost of Britain, likely linked to the deep ones and Cthulhu, and specifically to Ahu-Y’hloa, the mighty deep one city off the coast of Cornwall. The fact that Bran the Blessed, mightiest son of Llyr, was a giant in folklore suggests not entirely human blood – perhaps he was an unusual deep one mutation.

GWYN AP NUDD, Great One. It is not possible to hunt the boar Trwyth without Gwyn, the son of Nudd, whom God has placed over the brood of devils in Annwn, lest they should destroy the present race.

– “Culhwch and Olwen,” The Mabinogion

Gwyn the son of Nudd, Gwyn the White, Gwyn the Hunter, Gwyn the Master of the Wild Hunt, Gwyn the Lord of Castle Revolving. Of all the rulers of the Tylwyth Teg, it is said the Gwyn ap Nudd is the mightiest, save perhaps for his brother Arawn the Gray. In his true form he looks like an especially beautiful fey, with hair of shining silver and skin of purest white. He often wears a crown of flowers and stag’s antlers, and war will blacken his face with charcoal.

Though, like all Tylwyth Teg, Gwyn pursues numerous schemes in a desperate attempt to escape boredom, his favourite diversion is always hunting. On certain dark nights he will lead the Wild Hunt across the sky, pursuing any poor mortals he finds, but Gwyn prefers mightier, more monstrous prey. He claims to be the son of Nodens (“Nudd”), the greatest hunter of them all, and dedicates many of his kills in that elder god’s name. None know for sure if King Gwyn is telling the truth, but he does seem to have great mastery over the nightgaunts.

Nyarlathotep often takes Gwyn ap Nudd’s form, so it is very dangerous to have dealings with the fey king. Though it is often hard to tell if an encounter with Gwyn was truly with him, it is generally assumed that the Gwyn ap Nudd who stole away Creiddylad and join King Arthur in his hunt for the boar Trwyth was the real being.

CULT: Few worship Gwyn ap Nudd as such, but offerings are still often left for the fairies in various parts of Britain. Certain sorcerers do invoke him in the hopes that he will lead the Wild Hunt against their enemies.

THE WILD HUNT: When vengeful or just bored Gwyn ap Nudd will often gather a great hunt to pursue someone who has angered him or to bring to heel some glorious quarry. The Wild Hunt usually happens in the Dreamlands, but if King Gwyn’s quarry is on Earth, he will pursue it then.

The Wild Hunt is led by Gwyn himself and generally includes 2D10+10 hounds of Annwn in dog form, 1D6+3 mounted Tylwyth Teg, and 2D6+3 Tylwyth Teg hunters on foot. However, sometimes other beings are drawn into the hunt as well, such as ghosts, nightgaunts, or hounds of Tindalos. Viewing the Wild Hunt causes a Sanity loss, as does even just hearing the terrifying wails, howls, and hooves across the sky.

ATTACKS: Gwyn ap Nudd acts with his weapons. He prefers not to use magic in combat, instead giving his prey a sporting chance. If he is facing a more dangerous foe, then Gwyn will use special arrows that cause madness (1/1D8 Sanity points with each hit). Then if things become especially dangerous, he can summon hounds of Annwn and Dreamlands monsters for protection.

GWYN AP NUDD, King of the Fairies

STR 21 CON 53 SIZ 12 INT 25 POW 25

DEX 25 APP 25 MOVE 12 HP 31

Damage Bonus: +2D6

Weapons: Sword 90%, damage 1D10 + db

Spear 90%, damage 1D10 + db

Arrows 90%, damage 1D8 + db + Sanity loss

Spells: Gwyn ap Nudd can summon Hounds of Annwn at the rate of one hound per magic point expended. In addition, he can summon any creature native to the Dreamlands that is either not connected to another deity or is loyal to Nodens by expending 1 magic point per SIZ point of the being summoned. He also knows all Contact Spells for any Tylwyth Teg Great Ones, Contact Nyarlathotep, Contact Nodens, and Summon Nightgaunt.

Sanity Loss: 0/1D10 Sanity points to see Gwyn ap Nudd in his true form. Seeing the Wild Hunt costs 1/1D8 Sanity (may be higher if the Hunt includes other Mythos creatures or entities). Just hearing the Wild Hunt costs 0/1D2 Sanity.

NODENS

Among the humans of Earth, probably none worshipped Nodens as much as did the Celts. As the great hunter of monsters, slayer of dragons, there was much to recommend Nodens to them. In fact, the mainland Celts worshipped Nodens under his real name, though the Brythons more often referred to him as “Nudd.” The relationship between him and Gwyn ap Nudd is open to debate.

NYARLATHOTEP

The messenger and soul of the Outer Gods has numerous avatars, some of which are of particular prominent to the British.

- Black Man. A Satanic figure that is often the leader of witches’ sabbats, including many in the British Isles. In this form he is frequently referred to simply as the “Evil One.”

- Dark Demon. This black pig-faced demon sometimes appears at the sabbats if Nyarlathotep wants something a little more dramatic than the Black Man.

- Gwyn ap Nudd. Though the king of Caer Sidi is a separate being, Nyarlathotep also will sometimes take his form as a personal avatar (enjoying the irony of pretending to be the self-proclaimed “son of Nodens”). It is often to know if one is talking with the real Gwyn ap Nudd or Nyarlathotep in disguise.

- Horned Man. Known as Herne the Hunter by certain cultists in east England, as well as the Wild Huntsman and Master of the Wild Hunt. A relatively recent persona created to mock Gwyn ap Nudd (as Gwyn was the traditional Brythonic commander of the Wild Hunt).

- Wicker Man. The embodiment of pagan sacrifice, who sometimes appears as part of certain rituals.

Note that he will frequently appear attended by Our Ladies of Sorrow, or sometimes they will be his heralds and messengers, delivering his commands.

SHUB-NIGGARATH

Numerous fertility cults have built up around her, and in various forms she was a favoured source of veneration for druids and Pictish shamans. As a result, many of her dark young have walked the island and some still remain in hidden forests.

- Green Man. Contrary to some reports, this is an avatar of Shub-Niggarath, not Nyarlathotep. Like the Great God Pan, the Green Man is Shub-Niggarath’s fertility embodied in a male form. He appears as a man made of leaves, vines, fruits, and other plant material all mixed together to form a humanoid figure. An ancient god of the druids, the Green Man has proven surprisingly tenacious despite Britain’s official Christianity. For example, his face is still carved in numerous churches and displayed on the sign of numerous inns, and his effigy (as “Jack-in-the-Green”) is danced around at May Day. The Green God, a Great Old One worshiped in the British village of Warrendown, is linked to the Green Man, and certain individuals worship them as the same being.

- Modron. The “Mother,” her most common avatar in Britain and the spiritual head of her ancient fertility cult. She appears as a large, voluptuous heavily pregnant woman whose features have a disquieting resemblance to the viewer’s own mother. As Modron Shub-Niggarath is relatively benign, content to receive worship and savour her sacrifices, and be served by her most beloved child, Mabon ap Modron (“Son, son of the Mother”). However, if she is ever angered or threatened, she will quickly transform into a more monstrous form.

SHUDDE M’ELL

King of the chthonians, called the “Great Dragon” or the “God of the Mound” in ancient texts. He was long worshiped by Picts, giants, and Little Folk, an embodiment of the wrath of the Earth and the powers of the tunnels. Numerous cairns, dolmens, and standing stones all over Britain are dedicated to the Great Dragon, many inscribed with various runes.

YOG-SOTHOTH

The Brythons have traditionally identified Yog-Sothoth not so much with a being but with a concept: the Awen. This is the spirit of inspiration that is the source of poetry, prophecy, and magic, but also madness, which can enter anyone at any opportunity to fill them with visions. Some scholars have related to this to the Christian Holy Spirit, but it has a far older origin. There are certain mountains, especially in Wales (such as Cadair Idris), that are considered close to the Awen, and it is said that any who sleep there come down either a poet or a lunatic. Some who sleep there also become pregnant with the “soul of the Awen,” — the most famous of these children of Yog-Sothoth were Merlin and Taliesin.

OTHER GREAT OLD ONES

- Byatis, Glaaki, and Eihort are all imprisoned in England’s Severn Valley and written about in the Book of Black Earth. Certain cultists enter Eihort’s labyrinth in the hopes of gaining occult power. Few return.

- Lilith, as the “queen of the witches,” is frequently worshipped alongside the Black Man at sabbats.

- Our Ladies of Sorrow. They often accompany Nyarlathotep, but also appear independent of him. They are always together and frequently spinning and weaving some strange design as they speak cryptic words to their guest. Our Ladies of Sorrow enjoy the fear and uncertainty that their prophecies cause.

- Saaitii the Hog, lord of the swine folk, has sometimes been summoned to Britain and is spoken of in certain rituals.

- Tru’nembra. The so-called “angel of music” that appears as a living sound, is also sometimes identified with the Awen.

THE MONSTERS

DRAGONS

Though the term “dragon” has been applied to numerous creatures, the most common ones are the chthonians and the lloigor. The chthonians are monstrous centipede-like monsters that burrow deep into the earth and cause numerous earthquakes. In ancient times, their worshippers often erected dolmens and burial mounds over the entrances to the chthonian tunnels, burying their greatest champions beside them so that their ghosts would be alongside the dragons forever. This connection with the cairns of ancient warriors (buried with their treasure) as well as the general link to the underworld with its minerals and gems, was what inspired the stories that dragons would guard great treasure troves. Indeed, certain gemstones seemed to have powers or ritual significance to the chthonians, and they would guard them jealously. They also known as the “worms of the earth” or the “black serpents of the barrow,” and are still worshipped by certain tribes.

Confusingly, the lloigor also inhabit their own tunnels underneath the earth, nursing their fading energies there, hoarding various minerals that they feel would help recharge their fading energies and taking humans are slaves. Many of them are found under the mountains of Wales, and as their physical form (when it manifests) resembles a great reptile, they have also contributed to many dragon tales. In fact, in pre-Roman times, many lloigor (who called themselves the “Dragon Kings”) demanded blood sacrifices be given to their stone oracles and statues. Some believe that Merlin’s vision of two dragons battling was actually a chthonian wrestling with a lloigor for control of a mountain.

Other reptilian monsters have also added to the stories, such as the hunting horrors of Nyarlathotep (presenting the image of dragons as flying predators).

GIANTS, Lesser Independent Race.

He is not smaller in size than two of the men of this world… and he has a club of iron, and it is certain that there are no two men in the world together who could lift that club unburdened. And he is not a comely man, but on the contrary he is exceedingly ill-favoured, and he is the woodward of that wood.

– “The Lady of the Fountain,” The Mabinogion

It is said that before the first humans came to Britain, the giants ruled. Some say in ages past they were human, but that somewhat caused their size to swell. Others believe that the giants are the descendants of blasphemous cross-breeding between humans and gugs or that they are the descendants of Atlantis or originally came from the Dreamlands or were indeed the figures mentioned in Genesis: “There were giants in the Earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men…” Whatever their origins they have been living alongside humans, and warring with them, for many ages. Of course, not every encounter with a “giant” is with an actual giant. Gugs, trolls, voormis, and many others have been confused for them.

Though millennia ago they were the masters of all survey, humanity has pushed back giants to the edges of civilization. Those few that remain on Britain are found on isolated islands or the mountains and hidden valleys of Scotland and Wales, or have moved to subterranean tunnels. They have ancient pacts with the Little Folk and the Worms of the Earth, and many giants worship the Mother (Shub-Niggurath) and the Great Dragon (Shudde M’ell), and some even the Piper (Nyarlathotep). Most dream of a day when they can drive humanity from Britain and reclaim it for their own.

The “average” giant appears as a rough and savage figure twice the size of a regular human, though it is a species prone to mutation. Some giants are much bigger, others have a single eye and/or a single leg, some have horns, etc. They breed true with humans and their bloodlines have been so mixed with humanity that many giants give birth to humans and some humans will give birth to giants.

ATTACKS: most carry giant clubs, though some have metal weapons. Many also throw stones.

GIANTS, Original Lords of the Island

char. rolls average

STR 3D6+20 30-31

CON 3D6+8 18-19

SIZ 5D6+10 27-28

INT 3D6 10-11

POW 3D6 10-11

DEX 3D6 10-11

Move 12 HP 23

Av. Damage Bonus: +2D6

Weapons: Club 50% 2D6 + db

Punch 50% 1D8 + db

Thrown Rock 40% 2D6 + db

Armor: 2-point hide

Spells: Giant wizards known 1D10 spells

Skills: Hide 30%, Spot Hidden 40%

Sanity Loss: 0/1D8 Sanity points to see a giant.

GOBLINS

These are more properly known as the “gof’nn hupadgh Shub-Niggurath” — the blessed of Shub-Niggurath, or as they are called in Welsh, the Bendith y Mamau (“Blessing of the Mothers”). They are beings who have been sacrificed to Shub-Niggurath and then “birthed” again from her body. Though conventionally most goblins have goatish features, those birthed by Modron are more likely to have pig or deer traits (tusks, curly tails, antlers, etc.), but others have other strange deformities. The goblins are sometimes accompanied by the “treeherds,” which are in fact the dark young of Shub-Niggurath.

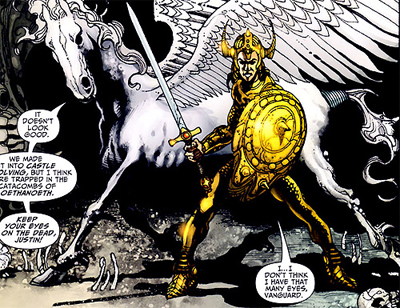

HOUNDS OF ANNWN, Lesser Servitor Race.

He heard the cry of other hounds, a cry different from his own…. Of all the hounds that he had seen in the world, he had never seen any that were like unto these. For their hair was of a brilliant shining white, and their ears were red, and as the whiteness of their bodies shone, so did the redness of their ears glisten.

– “Pwyll, Prince of Dyved,” The Mabinogion

A species of shape-shifters that hunts through the Dreamlands was domesticated by the Tylwyth Teg. In their true form, they appear as a shifting mass of white mist in which various body parts form at random moments. These beings have been domesticated by the Tylwyth Teg, who have them transform into both the Teg’s hounds and their steeds, and they are utterly devoted to their fey masters.

The howl of the hounds of Annwn on the hunt is incredibly disturbing and reverberates across the sky. The strangest thing about the sound is that it actually gets quieter the closer the hound gets, so that if you are right beside one, the howling sounds only like a murmur.

INVISIBILITY: Hounds of Annwn can turn invisible at will by spending only a single magic point. However, they can only attack when visible.

SHAPE-SHIFTING: Hounds of Annwn can make themselves appear as any beast (never a human-like form). The Tylwyth Teg find them most useful as horses or dogs, so they will generally appear as such. No matter what form they take, they are always white with red eyes and red in the insides of their ears.

TRACK: When they scent their prey, they can follow the scent to any part of the Dreamlands or Earth. The only way to escape the scent is to travel to another planet. Or to either kill the hound or convince its fey master to call off the hunt.

TRAVEL: A hound can run across the sky as easily as on land, and can at will move between Earth and the Dreamlands, taking its rider with it.

ATTACKS: A hound of Annwn uses whatever attack is appropriate for its form, but always inflicts the same damage. If in dog form when facing an especially dangerous foe, the hound will often grow to horse-sized but still keep its hound appearance. If panicked, it will take its natural form.

HOUNDS OF ANNWN, Fey beasts

char. rolls average

Str 3D6+20 30-31

CON 3D6+12 22

SIZ 2D6+1 8

(4D6+12) (24)*

INT 3D6 12

POW 4D6 14

DEX 4D6 14

Move 20 / 20 flying HP 15 (23)*

*The number outside the brackets is when dog-sized, inside is horse-sized

Av. Damage Bonus: +2d6

Weapons: Bite/hoof 90% 1D10 + db

Armor: 2-point hide

Skills: Dodge 50%, Hide 70%, Spot Hidden 80%, Track by Smell to the Ends of the Earth 120%

Sanity Loss: 0/1D2 Sanity points to see it disguised or to hear its howl upon the wind; 1D3/1D20 Sanity points to see it in its true form.

MEN OF THE BARROW

Certain warriors, shamans, and other devottees to the Old Gods, especially Shudd M’ell, are buried in tombs and barrows. Because they have been “blessed” by their deities, they are not dead, but merely sleeping. If their tombs are broken into, the men of the barrow will attack. Treat as mummies.

MERFOLK

The merfolk from the sea seducing mortals and leading them to their doom comes from stories of the deep ones. In fact one of the three major cities of the deep ones is Ahu-Y’hloa, off the coast of Cornwall.

SWINE FOLK

These subterranean piggish humanoids make their home in some parts of Wales, dwelling under certain of the mounds and worshipping Saaitii.

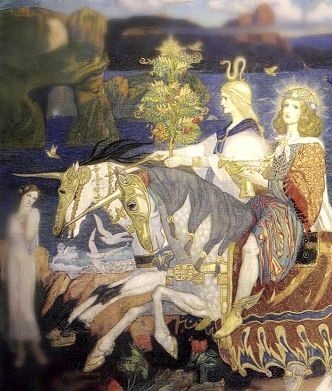

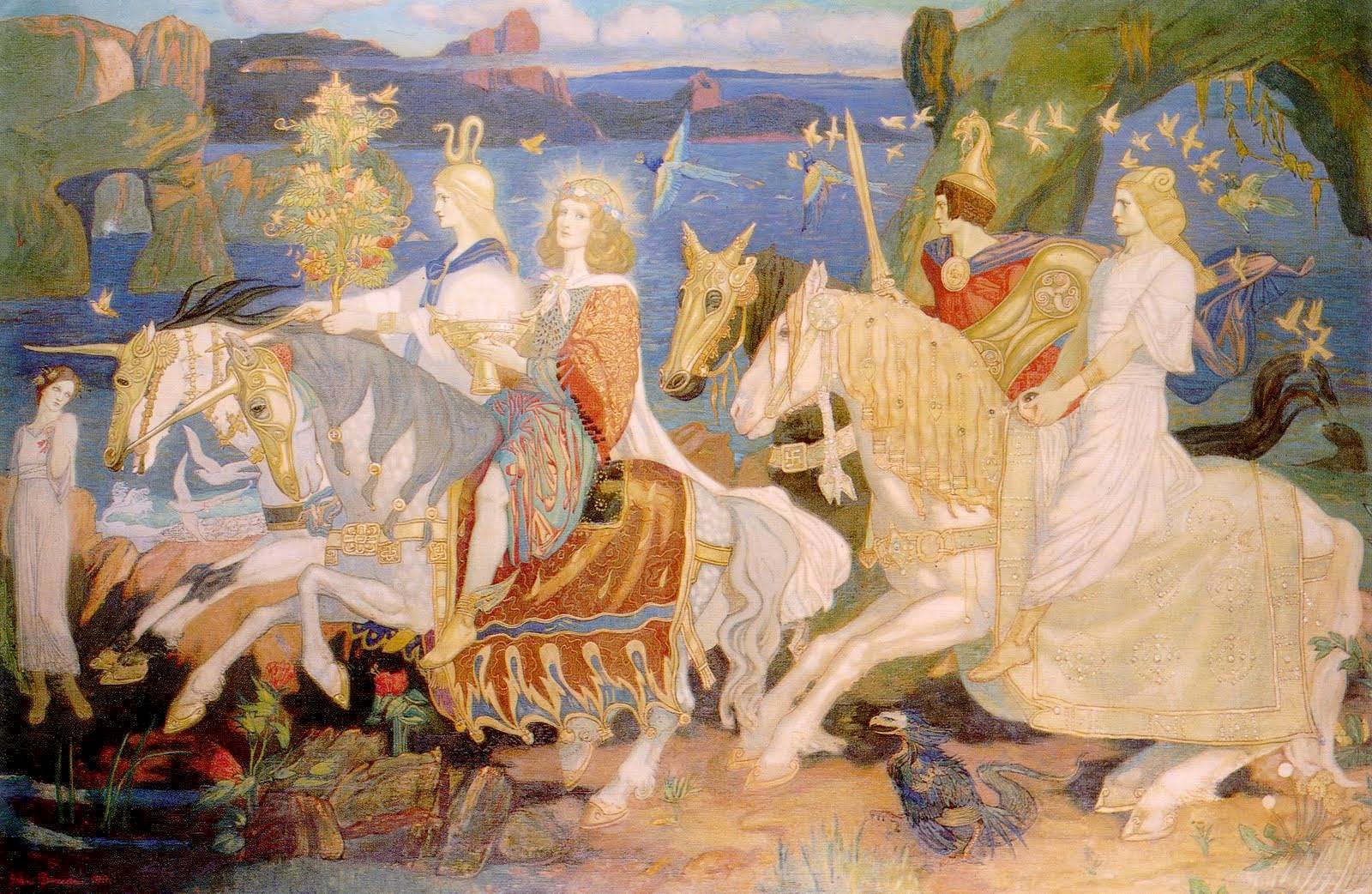

TYLWYTH TEG, Lesser Independent Race.

While he sat there, they saw a lady on a large pure white horse, and with a garment of shining gold around her, coming along the road that led from the mound. The horse seemed to move at a slow and even pace… and he followed as fast as he could [but] the greater was his speed, the further was she from him.

– “Pwyll, Prince of Dyved,” The Mabinogion

The Tylwyth Teg or the “Fair Family” — beings later known as the “fairies” — are a civilization of human-like beings who inhabit the Dreamlands (which the Brythons call Annwn – the “Otherworld”). Some believe that the Tylwyth Teg were original human thousands of years ago, but if they were, they are not quite human anymore. They do appear, in their natural form, as beings of almost impossible beauty with thin, graceful bodies, shining golden hair, golden eyes, and pure white skin. So strangely beautiful are they that it is difficult on them. Each Tylwyth Teg also has a specific human form they can take, which they use to walk among mortals.

The Tylwyth Teg never grow old. As the centuries go by, they merely become more powerful and more jaded, with their leaders being Great Ones (the gods of the Dreamlands). Though the Tylwyth Teg pretend to not worship any gods besides themselves, as lords of the Dreamlands they are ultimately subservient to Nyarlathotep and also venerate Hypnos, the king of dreams, and Nodens the Hunter (whom they call “Nudd”). It amuses Nyarlathotep to sometimes masquerade as Teg rulers, especially Gwyn ap Nudd.

Pride and boredom are the two defining traits of the Fair Family. They are all very old and very powerful, and have done so many things many times that to do almost anything again would be a horrible burden. Thus they are obsessed with novelty. The Tylwyth Teg scorn regular humans as their inferiors but they also seek to play games with them in order to try new things. The Tylwyth Teg often kidnap humans and force them to entertain them or will develop complicated schemes that they ensnare humans in, just to see what they will do. The Tylwyth Teg are too far-gone from any mortal perspective to fully comprehend why encounters with the Mythos cause humans to go mad, but many of the fey do find such reactions amusing, and so sometimes lead victims into a monster’s web. However, just as many Tylwyth Teg are hungry for hunting, and battling alien monstrosities to the death is one of the few things left that gives a certain zest to existence.

ANNWN: Though the name “Annwn” can refer to the entire Dreamlands, it can also refer to the domains of the Tylwyth Teg in particular. There are entrances to Annwn all over Britain, often marked by a hill, a cairn, a standing stone, or a ring of mushrooms. Any Tylwyth Teg who stands at one of those entrances can open it with a magic point, allowing him and his companions to enter the Otherworld. He can also return from Annwn to that place with a magic point as well.

The cities of the Fair Folk can look like whatever they want, but often appear white and gold. Time runs differently there, so sometimes a mortal might spend a day in Annwn and return to find a hundred years have passed or spend a year in Annwn but no time has passed on Earth.

ATTACKS: They attack with various regular weapons, favouring elegant swords, spears, and longbows. All Tylwyth Teg known sorcery, and they are not afraid to use it against their enemies. Many of them dip their weapons (especially their arrows) into a certain poison that can bring madness to those it infects (0/1D6 Sanity points with each hit).

TYLWYTH TEG, the Fey Folk

char. rolls average

STR 2D6+6 13

CON 2D6+6 13

SIZ 3D6 10-11

INT 2D6+12 19

POW 2D6+12 19

DEX 2D6+8 15

APP 2D6+12 19

Move 8 HP 11-12

Av. Damage Bonus: +1D6

Weapons: Sword 40% 1D8 + db

Spear 40% 1D8 + db

Arrows 60% 1D8 + db + potential Sanity loss

Armor: none natural, but they may carry armour

Skills: Hide 60%, Listen 40%, Sneak 60%, Spot Hidden 40%

Spells: all know at least 1D6 spells. Furthermore, any Tylwyth Teg can spend 1 magic point to appear human – each Teg has a very specific human form that they can take.

Sanity Loss: 0/1D6 Sanity points to see a Tylwyth Teg in their natural form.

OTHER FEY

At various times other beings besides the Tylwyth Teg have been confused for fairies:

- Little People. A stunted humanoid race that has been pushed back into the edges of the wilderness (especially the mountains and valleys of Wales). Contrary to some claims, these are not the Picts, but they have shared the island with the Picts for a very long time and there has been a certain amount of interbreeding. They worship a pantheon that has the Mother (Shub-Niggurath) at the head, but also includes the Piper (Nyarlathotep), the Hunter (Nodens), the Seer (Yog-Sothoth), and the Dragon (Shudde Me’ll). They often kidnap human children for their dark rituals. Some are halfbreeds with the serpentine worms of the earth.

- Worms of the Earth. Though this is a term frequently applied to Chthonians, it can also refer to remnants of the serpent people who turned to worship Tsathoggua and so were cursed by Father Yig. These “worms of the earth” or “children of the night” still worship Tsathoggua and a mysterious Black Stone, and are responsible for many of the curses identified with the fairies in folklore. Like the Little People, they also kidnap children for their rituals.

VOORMIS

Though many wild men are humans who have gone insane, there are also voormis prowling the wilderness, mistaken for men who have gone made and animalistic.

WEREWOLVES

Shub-Niggarath in her avatars of Modron and the Green Man, as well as Nyarlathotep as the Horned Man all enjoy punishing mortals by transforming them into ravening beasts. Fey lords such as Gwyn ap Nudd also enjoy this. They in particular enjoy unleashing their victim upon his friends, so that the werewolf (or werebear, wereboar, etc.) destroys those closes to him. Some also seek to become werewolves willingly, such as Gurgi Rough-Grey and his pack, who dedicated their victims to Shub-Niggarath and then devoured their hearts.

Half-Giant

Half-Giant Ellylon

Ellylon Goblin

Goblin Half-Demon

Half-Demon

If you told people you were looking for a modern retelling of the original version of King Arthur, they’d likely assume you meant a pseudo-historical one and would most likely direct you towards Mary Stewart’s Arthurian series: The Crystal Caves, The Hollow Hills, The Last Enchantment, and The Wicked Day. The first three star Merlin while the final one focuses on Mordred, and they’re the most famous Arthur stories that are grounded in the actual 5th century rather than Mallory’s pseudo-middle ages with knights and tournaments and whatnot.

If you told people you were looking for a modern retelling of the original version of King Arthur, they’d likely assume you meant a pseudo-historical one and would most likely direct you towards Mary Stewart’s Arthurian series: The Crystal Caves, The Hollow Hills, The Last Enchantment, and The Wicked Day. The first three star Merlin while the final one focuses on Mordred, and they’re the most famous Arthur stories that are grounded in the actual 5th century rather than Mallory’s pseudo-middle ages with knights and tournaments and whatnot. Le Morte d’Arthur

Le Morte d’Arthur King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table.

King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table.