With the exception of King Arthur himself, Merlin is the most famous character from Arthurian folklore. He defines the wizard archetype so perfectly that whenever an English story references some wizard, it’s usually Merlin, even if otherwise King Arthur doesn’t make an appearance. He’s part of the backstory in everything from children’s fantasy such as Harry Potter and The Talking Parcel to superhero tales such as Black Knight and The Demon. Like King Arthur, Merlin’s name is so well-known and so linked to an archetype that people often don’t realize how little they know about the character. They just think “yeah, Merlin – he’s an important wizard. I know what wizards are like – big white beard, staff, pointed hat, and either a traveler’s cloak or a robe full of stars. He can do all sorts of crazy magic and is a benevolent mentor to heroes.” However, Merlin’s origins are a lot more complex. Appropriately for a shapeshifter, Merlin’s story has taken on many forms.

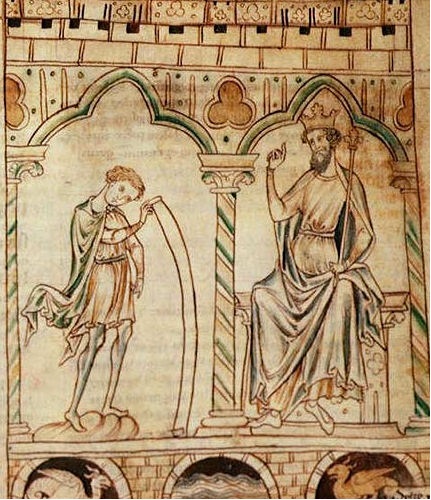

Like many legendary figures, King Arthur originally existed in a largely oral tradition. It was the 12th century that gave us the first cohesive biography of Arthur, with his prominent appearance in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain. This book was also the first appearance of Merlin. His mother was a virgin princess and his father some sort of spirit (a demon or a fairy – it’s not proven which), which has granted him the gift of prophecy. As a boy, Merlin reveals to the British tyrant Vortigern that his tower keeps falling because underneath it a red dragon battles a white dragon, which predicts how Vortigern will be defeated by Ambrosius, whose throne Vortigern has usurped. After Vortigern’s defeat, Merlin becomes the advisor of King Ambrosius. Later Merlin transports Stonehenge from Ireland to Britain to serve as a memorial for the British slain by Saxon treachery, prophecies Ambrosius’ death and the coming of King Arthur, and finally disguises Ambrosius’ brother Uther Pendragon as Gorlois in order to sleep with Gorlois’ wife Igraine and produce Arthur.

In many ways, this Merlin is similar to the later one of more familiar stories. He is already performing many of his most memorable feats, such as moving Stonehenge and transforming Uther. He prophecies King Arthur. He is half-human. However, this Merlin never meets Arthur directly and he isn’t really a wizard. Merlin’s only explicitly supernatural ability is prophecy, and he transports Stonehenge through vaguely defined “machinery” and uses “medicine” to change Uther’s appearance. You’re supposed to view him as scholar and scientist rather than a magic-user – a startling notion to appear in a medieval text.

Later authors would turn Merlin into a full-blown wizard as well as have him stick around long enough to guide King Arthur in his early years. Not only would he transport Stonehenge and transform Uther through magic, but he would also perform numerous other supernatural feats – many of them involving changing his own form or others. These authors also made Merlin a more morally ambiguous figure – presumably because they felt any wizard (even one whose ultimate goal was good) could not be entirely virtuous. He’s still on the right side, King Arthur’s side, but behaves horribly when not on his mission. This Merlin loves to toy with people, refusing to explain himself and only telling people what he needs to in order to get them to do what he wants. He chuckles when he gazes at people’s future and sees they’ll die an ironic death. He sexually harasses his apprentice Nimue until she entombs him in a tree. This is the Merlin of the Arthurian romances, and especially Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur – the most famous Arthurian text.

The character of Merlin gets transformed again in modern stories, such as T. H. White’s novel The Once and Future King and John Boorman’s movie Excalibur. These authors smooth out a lot of the rough elements of Arthurian heroes, such as King Arthur’s vengeful pride, Lancelot’s berserker rage, and Merlin’s disquieting nature, making them unequivocally heroic. Now Merlin is an entirely benevolent wizard, King Arthur’s kindly mentor, and surrogate father figure. In the Sword in the Stone installment of Once and Future King, Merlin is even Arthur’s tutor, transforming him into various animals to teach him about life. This is the Merlin most modern people think of – friendly bearded guy giving useful advice and casting some fancy spells. This is the Merlin that inspires Gandalf.

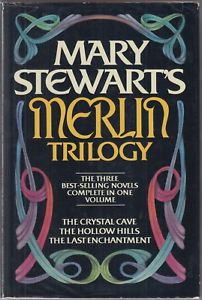

Sometimes earlier versions of the character still make appearances. Mary Stewart’s series of Arthurian historical fiction leans into Merlin being a prophet and scientist instead of a wizard, and the first book (The Crystal Caves) closely adapts Merlin’s appearances in History of the Kings of Britain. Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court features Merlin as a manipulative charlatan and Phyllis Ann Karr’s Idylls of the Queen has him as a fanatical lunatic.

Perhaps the most complex exploration of these different versions of the character is Merlyn in Marvel Comics’ Captain Britain and Excalibur – when he first appears to give Captain Britain his power, Merlyn (or “Merlin”) appears as the benevolent father figure of Once and Future King to Brian “Captain Britain” Braddock, but later this proves to be a façade as the true Merlyn is a far more amoral manipulator, like the Merlin of Malory and the Romances. It’s implied he went all T. H. White because that surrogate father-figure and tutor is who Brian would most respond to, fulfilling a hole in the lonely boy’s life and appealing to his childhood fantasies of being a knight and belonging to something greater than himself. A Malory Merlin pretending to be a White Merlin to manipulate someone into doing what he wants is very on-brand. Later, the character seems to be invoking the original Geoffrey of Monmouth scientist Merlin as a lot of the character’s “magic” is revealed to be alien science – he’s even linked with the Doctor, the hero from the British science fiction show Dr. Who. It’s hard to know how much of this is intentional, especially because figures such as Geoffrey of Monmouth are rarely read these days except by medieval scholars. However, it is intriguing that these Marvel comics do seem to be engaging with all versions of Merlin, whether accidentally or on purpose.

Many King Arthur characters are vastly different from themselves in different interpretations – Queen Guinevere in particular has a talent for appearing as a virtuous hero or a sinister villain or anything in between, depending upon the needs of a particular story. But I’m especially fascinated by how different these versions of Merlin are. If the Merlins of Geoffrey, Malory, and White all hung out together, they probably wouldn’t like each other very much.

One of the reasons I love the stories of King Arthur is that they’re so mutable, able to be changed into whatever purpose they’re needed. It’s fitting that one of the changeable parts is the nature of Merlin, the shapeshifting wizard who is most famous for helping Uther Pendragon take on a different form.

If you told people you were looking for a modern retelling of the original version of King Arthur, they’d likely assume you meant a pseudo-historical one and would most likely direct you towards Mary Stewart’s Arthurian series: The Crystal Caves, The Hollow Hills, The Last Enchantment, and The Wicked Day. The first three star Merlin while the final one focuses on Mordred, and they’re the most famous Arthur stories that are grounded in the actual 5th century rather than Mallory’s pseudo-middle ages with knights and tournaments and whatnot.

If you told people you were looking for a modern retelling of the original version of King Arthur, they’d likely assume you meant a pseudo-historical one and would most likely direct you towards Mary Stewart’s Arthurian series: The Crystal Caves, The Hollow Hills, The Last Enchantment, and The Wicked Day. The first three star Merlin while the final one focuses on Mordred, and they’re the most famous Arthur stories that are grounded in the actual 5th century rather than Mallory’s pseudo-middle ages with knights and tournaments and whatnot.