Tags

“Ah, Geraint,” said Gwalchmai, “is it thou that art here?”

– “Geraint ap Erbin,” The Mabinogion

“I am not Geraint,” said he.

“Geraint thou art, by Heaven,” he replied, “and a wretched and insane expedition is this…. Come thou and see Arthur; he is thy lord and thy cousin.”

“I will not,” said he, “for I am not in a fit state to go and see any one.”

Thereupon, behold, one of the pages came after Gwalchmai to speak to him. So he sent him to apprise Arthur that Geraint was there wounded, and that he would not go to visit him, and that it was pitiable to see the plight that he was in. And this he did without Geraint’s knowledge, inasmuch as he spoke in a whisper to the page. “Entreat Arthur,” said he, “to have his tent brought near to the road, for Geraint will not meet him willingly, and it is not easy to compel him in the mood he is in.”

The stories of King Arthur is one of those funny things that have conjured so many cultural tropes and images that a lot of people think they know more about it than they actually do. For example, I’ve heard people comment that they prefer characters who are more complicated and flawed, and so perfect heroes such as King Arthur and his knights are not interesting.

But King Arthur and his knights are so deeply flawed. One of the most regular themes in the Arthurian Romances is how great ideals and moral codes crumble and break eventually. The whole arc of Arthur is that he created the perfect kingdom but it was inevitably destroyed – not by an outside force, but rotting from within due to the sins and weaknesses of the knights. Infidelity, petty jealousy, incest, betrayal, feuds, vengeful murder – all of these help to shatter the Round Table. So does madness.

It is fascinating to look at how older cultures viewed mental issues, especially things like anxiety or depression, where it is often ambiguous whether the person is suffering from a disorder or if that’s just their personality. In King Arthur stories, characters are frequently pushed to the breaking point by traumatic events, when their views of themselves are destroyed.

The most famous break is with Lancelot. He is seduced by the princess Elaine when she’s disguised as Guinevere, and once Lancelot realizes that she wasn’t the woman he thought she was, he leaps out of a window and runs screaming into the forest. It’s an ironic scene, for if he had had sex with Guinevere, that would have been the supreme betrayal of his vows to King Arthur, and yet it is having sex with Elaine that shakes Lancelot to the core. He feels he cheated on the queen, sullied himself with someone he didn’t love, and so he lives like an animal in the wild for several years.

The theme of trauma reducing a man to an animal shows up in several Welsh Arthurian stories as well. In the Welsh version of the “Lady of the Fountain,” the hero Owain temporary leaves his fairy wife, the Lady of the Fountain, to return to King Arthur’s court. He becomes so wrapped up in Arthurian adventures that he forgets to return to her, and after waiting months for his return, the Lady eventually discards him as he discarded her – appearing to him in court to deride his faithlessness and then using her magic to hide her valley from him forever. Owain goes mad with the guilt and loneliness, and he spends the next few years living naked in the forest, eating raw meat. Similarly, the semi-historical Myrddin (who the Arthurian Merlin was partly inspired by) in “The Life of Myrddin” was traumatized by his involvement in a great battle, and so fled naked into the forest, where he ate moss and apples, befriended the beasts, and refused to return to human society, snarling like a wolf whenever someone tried. It is perhaps problematic to identify someone in the middle of a nervous breakdown as akin to a wild beast, but a storm of emotions causing someone to flee into their head and into the wilderness is a feeling I can strongly identify with. Sometimes so much force is exerted on the self that one wishes for the self to be blotted out.

“Geraint ap Erbin” is another Welsh Arthurian story in which the warrior suffers from mental issues, but in a dramatically different way. The first half of the story is about Geraint winning the lady Enid by impressing her in a tournament, a pretty traditional Arthurian Romance. The second half involves Geraint being forced to leave Arthur’s court to take charge of his father’s domain in Devon, giving up his adventures to instead become a ruler and bureaucrat. Geraint hates this, constantly yearning for Arthur’s court, and eventually shuts himself in his room, too depressed to deal with any part of the court. Geraint believes that since he can no longer be a warrior and adventurer, he’s a failure as a man, and so he starts to suspect his wife Enid of infidelity – deciding that there’s no way that she could ever love a failure like him. In a storm of envy and depression, he drags Enid with him out of Devon, determined to fight battle after battle in order to prove to her and himself that he is still a man… or die in the attempt.

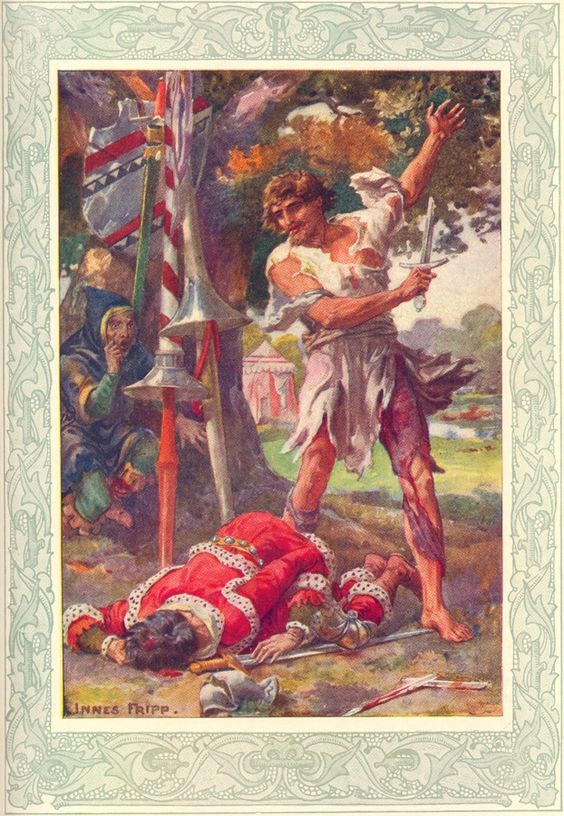

Geraint’s suicidal obsession and his verbal abuse of Enid ring much more realistically than the other characters’ descent into animalism, which makes it especially shocking to read. There’s an intense moment where Arthur finds Geraint almost dead from numerous wounds, both he and Enid dressed in tatters, and the king is angry and frightened – demanding to know why Geraint is putting himself and Enid through hell. It is very hard for people who don’t suffer from depression or anxiety to understand exactly why we who do are acting the way we are – it seems illogical, bizarre, and self-destructive (and often is); this moment in the “Geraint” Romance is startling for its psychological realism.

There are various examples in stories all over the world of characters struggling with mental issues. What makes the Arthurian stories that struggle with this topic especially striking is that King Arthur and his knights are supposedly archetypes of masculine heroism and strength, perfect paladins pure of thought and deed. By showing them being undone by their guilt, self-hating and self-destructive because they fall short of their ideals, it reminds us that depression can strike down all of us. All of us are vulnerable, even the greatest knights of the world.